Both of us at NSD were in the same graduating class as the Columbine shooters, so, while we were mercifully spared much of the security theatre to which students have been subjected ever since, we did come into (legal) adulthood and the subsequent ability to purchase our own media at the exact time that media was most villainized. Sure, we had been around for the fervor surrounding games like Mortal Kombat (a definite favorite at our middle school), but in 1999, the anti-game crusaders had something they didn’t in 1993: a body count, brought about by perpetrators who, being dead, could be ascribed any motive or influence one could think of. Doom (a definite favorite at our high schools) was seized upon, likely because the name was remembered from those 1993 hearings.

The period following this, as with so many aspects of the 2000s, seems disjointed and nonsensical to us now. Game opponents became national celebrities, meanwhile publishers produced games with ever-increasing amounts of violence and mayhem… while being surprisingly meek in defending them, often buckling under pressure. The games themselves split along ideological lines, though, between titles following the 1990s wave of crime movies (Grand Theft Auto III being both the most infamous and the most copied) and a post-9/11 glut of military games, many of which endlessly re-hashed WWII. Unsurprisingly, only the first category was deemed a threat to civilization. It’s telling that the only game actually designed to promote killing was given a free pass, since it was on behalf of the status quo - in this case, the US military.

Since then, as gaming has found an ever-widening audience, and game, on the whole, have largely moved away from the slaughter festivals of the early 21st century in other directions, all the panic and notoriety seems quaint. The fact that the blame for mass-murder events has laregly moved on to homophobia and transphobia, and even "wokeness" (whatever that is), reveals what we've known all along: the scapegoat has always been modernity, the changing world itself. The recent spate has even led to a renewed interest in the "Satanic Panic" of the 1980s as something of a Blameshifting Rosetta Stone, revealing the patterns that have recurred time and again.

But what about the violent games themselves? The question never should have been "do these cause a culture to become more violent," but rather, "what does it say about a culture that its stories, particularly those told through forms of media, features violence so prominently?" Obviously, given the nature of this blog and the passions it follows, we aren't opposed to violent media - we've written lovingly about GTA: San Andreas and the nature of literal murder simulators, after all. But we should ask ourselves, once in a while, at least, why is it that these new and exciting worlds are viewed primarily from behind a gun or cockpit, why roleplaying systems dedicate so much effort to modeling combat (or, for that matter, why it features so prominently in games that can ostensibly be about anything at all)? Why did I have to struggle to come up with examples for one of my players who wanted to find a non-violent game to introduce their kid to the hobby? Why is it so prominent?To approach it from a macro level, combat condenses narrative, keeping all the basic elements white greatly narrowing their scope. Character motivations may be complex ("break through to deliver a message that will ultimately forge an alliance and greatly alter the outcome of world events") or simple (stopping that first guy from doing that). They may even be as straightforward as "don't die" or "do as much damage as possible before dying." How characters fight conveys their true nature: are they sneaky? Cool and professional? Self-sacrificing? Chatty and jokey? Left-handed? Not left-handed? If crisis reveals character, combat offers such circumstances without necessarily requiring elaborate setup. It can also serve as a narrative turning point, connective tissue linking scenes or allowing a story to cut between them: think of the Death Star sequences from the original Star Wars, and how the Stormtroopers show up to mark the start or end of a scene. In short, combat can be both visceral and functional, exciting and expository.

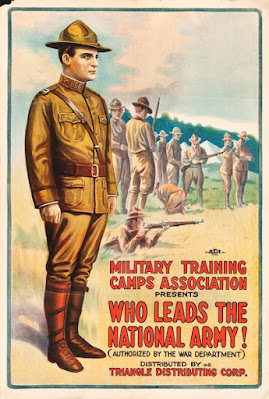

It can also be costly, at least in the real world, where the ugliness, brutality, and chaos of battle don't get to serve a narrative purpose. And exciting depictions and portrayals of combat have been used to entice the impressionable for as long as we've had art and language - America's Army is simply performing a similar role to the recruitment films of the 1940s, or of posters before that... In a way, there's something respectable about the honesty of this kind of messaging. We know what they're for, even if they have to sanitize harsh truths to fulfill their purpose. The same can't be said of media on the whole, though: there's a reason the U.S. military is heavily involved in almost every Hollywood production that depicts it. Police departments have similar relationships with media, particularly television, and "copagnda" has created the popular image of American policing far more than actual history and journalism. But, again, these are examples of conscious (if less visibly so) messaging. The status quo and established power structures can perpetuate themselves through popular culture without anyone directing it. Kids played "cowboys and Indians" and "cops and robbers" long before movies showed them how to do so, reaffirming through reenactment settler-colonial myths and the racist underpinnings of the carceral state. Movies helped keep the cycle going, though, as did comics, radio, television, and, once again, games.

So, what's the takeaway, then? Violence is too omnipresent in our stories to completely avoid, and this certainly isn't a new phenomenon - quite the opposite. (I bring up the Illiad so much in this blog, I really should read the thing.) I do think, however, that context matters. We can watch, read, or play a scene and think about what it's trying to say, what purpose it serves, and what are its implications. Is it the right thing to do? Is it the thing this character would do? Taking the time to consider the humanity (or whatever the appropriate term would be for a given non-human species) of everyone involved, particularly enemies, can help to counter some propagandistic elements. How are they experiencing this fight? What do they want out of it? What outcomes would they consider favorable? When we're creating our own, whether at the table, onscreen, or on the page, it's worth it to ask "is this fight necessary?" Even if it's specifically what the players are there to do (as will be the case with many electronic games), it should feel like it matters, that it's not simply rote. Finally, be sure to provide options, whether they're to avoid combat entirely or to approach it non-lethally. Two of my favorite electronic game series, Metal Gear Solid and Dishonored present the player with lethal and non-lethal approaches, with different consequences depending on which is taken. I always go for the latter, maybe because I want to be more like Batman, or maybe because it's not something I get to see as often.

Violence in narratives will not be going away, regardless of what gets blamed upon it, but it's on us as audiences and as storytellers to decide whether it's appropriate and what kind of message it's sending, to break the patterns of repition and reinforcement... and that's a fight worth taking on.

- B

Send comments and questions to neversaydice20@gmail.com or Tweet them @neversaydice2.