The knee-jerk answer you tend to get is "nostalgia," that people long for the days of their youth when life (and games) were simpler. And while one can certainly feel nostalgia for a time period they did not experience (a central theme of one of our two US political parties), the sheer number of new players discovering games from before their time suggests more here at play.. if you'll pardon the expression. It's something I first noticed a few years ago at a MAGFest, where many of the attendees were younger than me, but huge fans of games released when I was a kid... long before most of them were even born. The same goes for the randomizer and speedrun communities based around playing older games in ways... other than originally intended. But even when approached the same way as when they were first released (with a few "quality-of-life" improvements like save states and even rewind functionality), people are connecting with older games, and not necessarily ones they have fond memories of.

You'll get different definitions of the "retro" part in retrogaming, depending on who you ask. Some people will count any system that's no longer in production. Some will say that it's anything released a certain number of years ago, usually ten or twelve (the latter essentially describing the "8-bit" era starting with that Atari 2600 in 1977 and the the release of the Sega Mega Drive/Genesis in 1989). Personally, I go with a more concrete definition: the shift from standard definition (SD) games to high definition (HD) that took place with the seventh generation of console game systems (PS3, Xbox 360, and Wii... even if that last one wasn't actually HD). Besides the simple fact that games earlier than this are differentiated by taking some effort to play on modern TVs, most of the standards we take for granted today were solidified at that time, from the dominant formats (particularly third-person action games) to title distribution (digital games stored in onboard hard drives). Even if these consoles are older now than the Atari 2600 was when the Genesis was released, they are essentially the same as those of today... the differences being primarily technical. There's been some variety, but, for the most part, electronic gaming has become standardized, at least when talking about wider-release titles (and consoles have never been as friendly to experimental indie games as PCs).

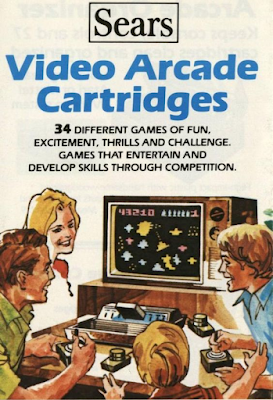

Prior to this, though, things were different, particularly in the days of 2D graphics where everything had to be abstracted to some degree. This required a similar approach to that of comics and cartoons, where simple images allow the audience to fill in the specific details themselves. Once graphic technology had reached a certain point, the visuals could take cues directly from this style of illustration (Mario, in particular, seems particularly influenced by cartoons of the 1920s and 30s), but in the early days, abstraction was near-absolute by necessity. Pac-Man is a yellow circle with a chunk missing to represent a mouth. Your spaceship is a small triangle. This squiggle is a major metropolitan city. The player's imagination fills in the rest. It's telling that this is an aesthetic that we keep coming back to through indie games and other retro-themed titles. When it was a requirement, though, other means were used to convey what the game could not, such as box art and illustrated advertisements. Modern usage rejects this, since the limited portrayal is the entire point. It's an interesting inversion, and one reason I think the original works tend to have staying power, whereas modern iterations tend to be forgotten quickly, or remembered for reasons other than their retro aesthetics (Hotline Miami and Return of the Obra Dinn, for example).The larger worlds that we create with these games are not necessarily escapist, either, and I'd argue that our involvement (complicity?) in the process is one reason behind that. In the same way that we see echoes of our own lives in dreams, they're just as present in the spaces between the pixels, or past the edges of the screen. They offer the potential to re-frame things, of an alternate perspective, and, for many, comfort. Another factor is sensorial: games closer to the arcade era were designed to overload the senses through bright colors and angular sounds - SHMUP fans in particular will cite the flow states they achieve with certain games, but the effect is hardly limited to that genre. They cut away our immediate surroundings, and there is only us, the game, and, as a certain Jedi Master once said, what we take with us.

In these times of ever-increasing stress and uncertainty, I'm sure I'm not the only who finds this space both refreshing and calming. No, the problems don't disappear while I'm saturating my senses with the full force of 8 and 16-bit intensity, but my perspective shifts for a bit. It's a breather, a reset. And playing the games isn't the only aspect of the hobby that helps, either - I may not be able to fix the world, but getting old systems running again is a reminder that I can do things myself, even if they're small. Plus, in an era of massive disorder and chaos, carefully archiving and sorting the games I have helps to put a little structure into one tiny area - maybe we can call it a form of electronic knolling. Part of it just knowing that I'll have them ready to go whenever I need them. That's the power of stories, and why we keep them around us, no matter their form. Now's a good time for all of us to get our collections ready, preparing our narrative bulwarks for the future.

- B

Send comments and questions to neversaydice20@gmail.com or Tweet them @neversaydice2.