The calendar tells us that it's October, and while it may not feel like it outside, this is officially the season for spooks and scares. Given the time of year and the twenty-year anniversary of its release (and also of my owning it) the next game in my backlog playthrough was obvious: 2001's Silent Hill 2. Much has already been written about this game (there's a reason it's on so many "Best Games of All Time" lists, after all), so this post will be neither explanation nor analysis, but rather a exploration of the way horror blurs the lines between the world that we know exists, and the way we feel it exists... and the way that games, both electronic and tabletop, are uniquely capable of embodying this dichotomy.

Given my love of horror and all things surreal, it's kind of surprising that it's taken me this long to actually finish the game. At the outset, it was because I felt obligated to play the original Silent Hill first, even though I was vaguely aware that the second game was its own standalone story. But even after I'd done that (getting the "worst" ending in the process), I only tried a couple more times, even while praise was starting to pile up. Maybe that was part of the reason - I felt that I had to play the game "properly" or I wouldn't get the correct experience, so I could only play at night, in the dark with headphones, alone and uninterrupted. But as with the other games in my backlog journey, circumstances finally lined up and, to borrow a phrase from an author who clearly influenced the Silent Hill series, the stars, at last, were right. It was October, my schedule was (very briefly) clear and the new RetroTINK 5x that replaced my late, lamented OSSC made the PS2 look gorgeous on modern screens. Even the weather seemed to cooperate, presenting me with a nearly lightless weekend that cut down on both screen glare and tonal dissonance. After all the buildup, I finished it off over the course of a week, and can confirm that it lives up to the hype.

Of course, I was hardly alone in seeking out this game, as PS2-era horror has seen an incredible resurgence in interest recently. (Apparently, even my own humble collection has become quite valuable.) But aside from market speculation, there's something that's drawing people to this specific era and style of game, a magic that has never been recaptured. Horror, in any medium, is driven by a sense of powerlessness, and "survival horror" games like the early incarnations of Silent Hill very much took this to heart, putting the player in the role of clumsy everymen who weren't particularly sturdy or capable combatants, heightening the sense of danger by limiting access to ammo and health items. While this had a strong appeal to a certain subset of players, it was far removed from the power fantasies that best-selling action games embody, and, as development budgets ballooned, wider sales became more and more of a necessity resulting in a conscious shift to bring the horror genre more in line with the widely-accessible mainstream.

The advancement of technology was a factor as well. Many of the defining features of survival horror came from trying to work around consoles' then-limited capabilities, keeping the environments sparse, often shrouded in fog and darkness, and enemies few in number, but exceedingly dangerous. All of this became less necessary over time, and, as graphical capability were further emphasized in heated console wars, even considered detrimental. As a result. the carefully curated environmental experiences were phased out in favor of flashier, more crowded worlds. I went into this Silent Hill 2 playthrough expecting frustration with the fixed camera, but experiences quite the opposite, and was frequently blown away by how good the locations looked despite the absence of modern 360-degree visibility. And, as anybody who has studied cinematography or film theory can tell you, the way a shot is framed is just as important as what it contains. Games with modern camera may be significantly easier to engage with, but at the cost of a very powerful visual storytelling tool.

It's an easy reading to attach the success of these games to the paranoia of the Post-9/11 era, but I don't think it's an incorrect one. While Silent Hill 2 was released before the attacks, the audience it clicked with was one that found their world suddenly dangerous and full of unexpected horrors, constantly ready for the next catastrophe. It's a mindset that, twenty years later, we can very much identify with, and Silent Hill 2, with its haunting depiction of a town where human activity simply stopped and themes of illness and disease incorporated into every aspect of environment and monster design, feels particularly appropriate in times of COVID and unrest, when everything seems to be falling apart around us. It feels right and correct, even in the absence of literal, direct explanation, and this is a framework that undergirds the most affecting works of horror and fantasy - something I've taken to calling "emotional logic."

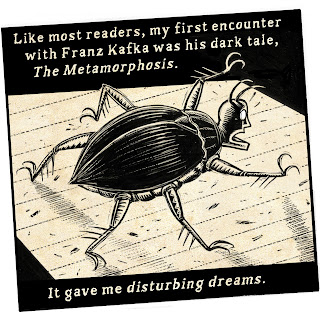

Emotional logic is a concept I first started to think about when I began reading the works of Franz Kafka, which seemed to fit neatly with the horror media I was consuming at the time, particularly the way the world seemed to shape itself to his characters' inner identities, the ones they tried to hide from others to maintain a facade of productive normalcy. The most famous example, of course, is in The Metamorphosis, in which a man named Gregor Samsa, frustrated with having to keep a job he doesn't care for to support his family finds himself transformed into a giant insect following a night of restless dreams. (A phrase, incidentally, that features so predominantly in Silent Hill 2, it was used as a subtitle in reissue editions.) There is no logical reason given, no internal explanation, it is simply something that happens - but it's consistent with Gregor's feeling, worries, and insecurities. Other works, like the unfinished novels The Trial and (especially) The Castle, expand this beyond the individual character into the structure of the setting and plot itself, creating byzantine structures both physically and societally, that mirror the protagonists' neuroses and fears. If that sounds familiar, it's essentially the same hook as the Silent Hill series, where the titular setting re-shapes itself as a twisted funhouse mirror of the characters' psyches.

Kafka himself is rarely considered a "horror" writer, and the concept of emotional logic doesn't simply apply to that genre. We also see it in the surreal nightmare and dreamscapes of Jorge Luis Borges and Italo Calvino, but also in the earlier incarnations of the fantasy genre, particularly in the Gormenghast series by Mervyn Peake, which builds a world of impossible architecture and obscure ritual for readers to lose themselves in, simultaneously alien and strange, yet eerily familiar. Even in the works of J. R. R. Tolkien, the ur-text of modern "high" fantasy, there are still echoes of this in the chaotic despair of Mordor and Mirkwood, along with the subtle machinations of Sauron's identity through the Ring and palantíri. These echoes carry through to the highly ordered and structured works of Tolkien-inspired fantasy media from the way magic, no matter how strict the "system" can never be ultimately understood as anything more than a manifestation of the user's will (and, sometimes, even subconscious) to the representation of alternate planes of existence, to even the design of the titular "dungeons" in Dungeons and Dragons, which are usually mapped around player experience rather than in a way that would make sense in their own universe.

It's in this experience that games, both tabletop and electronic, offer unique opportunities to explore the concept of emotional logic. While prose fiction allows an audience to build their individual landscapes according to description, games allow for interaction and development according to that audience's interest, whether it be through questions asked of a gamemaster or through spending time investigating the environment of an electronic game, and can operate outside the rigid structure of the understood and expected. To return to Silent Hill 2 as an example, towards the end of the game, when the protagonist's fragile mental state finally begins to collapse, even the simple functionality of things like doors is called into question, and going through them can lead to entirely different places rather than what "should" be on the other side. If this were attempted in a genre other than horror or fantasy, this would be a hightly undesirable effect, and most players would (rightly) say the game was "broken." But here, we view this not only as an acceptable possibility, we appreciate the creators' imagination in messing with basic concepts like spatiality - even when we aren't given the literal, direct reasoning behind it. Silent Hill is neither a fantasy world governed by "dream logic," nor is it a solid reality operating according to the expectations and assumptions we carry from our real-world experiences to most of the media we consume.

It's certainly not for everyone - the prominence of "[piece of media] Explained!" videos on YouTube shows that plenty of people feel like they need cogent, rational internal logic in a work to enjoy it. But they're not the only ones out there, as the popularity of works like Silent Hill 2 indicate. And gamers, of all varieties, are particularly poised to appreciate it if given a chance. After all, we're already accepting a table of statistics or handful of dots on a screen as being a person because we feel like they are. We're already participating in, to borrow a phrase from another of my favorite authors, a "consensual hallucination" every time we join our friends at a table or fire up our preferred electronic gaming platform. We're already creating totally new realities through our participation, so why limit it to the predictable rules of the world around us? We don't need to stray far for things to get interesting, revelatory, and, yes... even spooky.