It’s been quite a week in the world of tabletop RPGs, and, while it’s nice to see our little hobby featured in all kinds of media, we would have preferred it be for more positive reasons. Never Say Dice are by no means qualified (or up-to-date) enough to talk about the OGL kerfuffle, but the discussion around it did get us thinking about the nature of ownership when it comes to games. For an activity centered around the participants’ infinite imaginative possibilities, what does “ownership” of a system, setting, or even a session mean, exactly? What aspects of a game are inherent enough to have a brand name, and how much can the people at a table change things up before it starts to feel like something else? - B

A: The whole issue seems pretty broad, which is one part of the problem. Even if you only take a quick look at the idea of “ownership of a system,” it gets pretty complicated. Sure, there might be trademarks on specific things like Beholders, Mind Flayers and Displacer Beasts, but could you have something similar in designed game you designed yourself? You can have whatever you want! Just take a look at any of our previous inspiration posts from video games to other media that we’ve ported into roleplaying games -the issue really comes down to people making money from it. When you look at a game system in broader terms, though, strict ownership is hard to imagine. Can the concepts of tracking of a character's health, strength, or intelligence really be proprietary? Without delving into the legal complications, as plenty of people have done better than I care to at the moment, it seems not just hard to imagine, but ridiculous. Just look at the variety of ways health/lives are tracked in video games. While there have certainly been lawsuits over copyright infringement involving digital games, the core concept of tracking a character’s life essence, is something that spans a number of games, not a thing you can claim.

That isn’t really the crux of the recent issues though. People are fine with D&D owning the things D&D created: Their specific configuration of rules and strange monsters. The particular way in which they track the life essence of their universe’s denizens. Even their ownership of archaic, former edition rules like THAC0. Where people have rightfully gotten up in arms is in Hasbro/WotC trying to make it so they own or profit public creations. They, of course, claim that this never the intent... you can make up your own mind about what to believe. Should a company that produces typewriters own the documents typed on them? The tool in this metaphor is archaic, but the original D&D rules came about while typewriters were still popular. They are, in fact, both tools. One a mechanism for putting words onto paper, one a set of rules for putting stories to words. A different comparison might be another set of rules, such as the MLA or APA styles. Should the creators of these rules own all the dissertations from all the PhDs that used them? Of course that sounds preposterous, and rightly should. Could someone use a typewriter and/or the MLA to write horrible and hateful things? Sure they could -but I don't suppose that would “damage the brand” of the APA or Smith Corona. Perhaps the makers of D&D really were as afraid of this as they claim, but it's certainly doubtful that brand protection was the main intent. Generally, though, fear not. As long as you aren’t trying to make a profit, create your own worlds in whatever system you like. Alter the rules, they’ve always been just guidelines. These are your worlds, your rules and your games. WotC can’t take your tabletops away from you; not even the virtual ones. They can only make it harder to do what you love.

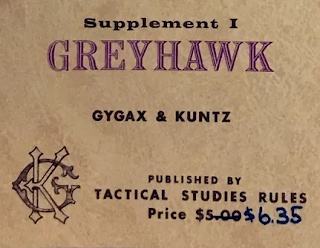

Which is, I think, both ironic and rather sad (if consistent with the system's previous ownership), as the world of D&D is itself a patchwork of borrowings from existing fantasy and horror authors. At least TSR put a few different systems out besides D&D to compete with other publishers' games in different genres! The sense of entitlement to player experience, though, is particularly gut-wrenching the more one thinks about it. This hobby is unique in that it allows for any possibility the people at the table can come up with (within the bounds of their agreement as to what's acceptable, a social contract that starts with the published rules and is then modified and altered through play). The publisher's role is to provide what Andy so eloquently describe as "tools." Once these tools are in the hands of the participants, the role of the publisher and all they represent (writers, artists, editors, playtesters, etc.) is to step back and, to borrow a phrase, let the game begin.

Does this mean that a publisher's "ownership" of a game ends as soon as play begins? Not entirely, no. Again, they largely control the "feel" a participant expects going into the game, and the text and other materials all influence the proceedings, even if they're being interpreted by the people playing. Rather, they become a silent participant themselves, neither controlling everything nor completely disregarded. A similar concept might come from the model seen in a different sense of "play": the creators of synthesizers and other electronic instruments, which form the backbone of most music produced today. While the sounds themselves (or rather, the programmatic instructions that create them) can be legally protected, the sounds' creators have no say in the music produced by users. Much of their business, then, is made by musicians hearing the work of other musicians using those products and purchasing their own. On the other hand, the musicians are under no obligation to list the manufacturers of their equipment, unless they're being sponsored. In a way, then, even the original OGL was rather insidious - it obligated people building from the materials provided by WotC to include language linking their work back to the corporate source when they really had no need to, just as their pre-OGL predecessors had not (provided they weren't backed into legal agreements crediting TSR, of course).

In a way, I don't think anyone can singularly "own" a game as its played. (The game, as a brand, is another story, but language gets tricky when it comes to IP, as we've talked about before.) It's not the players, or the GM, or the people involved in putting all the materials out there. It's a mesh of fine fibers suspended between points, originating from everyone involved. It's a beautiful communal activity, and needs to stay so.

Send comments and questions to neversaydice20@gmail.com or Tweet them

@nevers.aydice2 (while supplies last).